I suffered a severe LAD / widow maker heart attack and cardiac arrest. I had a fifteen Ejection Fraction (EF), and could not walk more than six blocks for several weeks after being released from the hospital. My doctor did not know who I was when I went into the office two weeks after suffering a cardiac arrest because the stent was not adhered to the artery wall. I was met by a series of questions from the doctor’s office nurse, “Who are you ? Why are you here? We have no record of you.”. A second nurse came into the office with a blank sheet of paper after my initial consultation, and asked me to start from the beginning. If I didn’t need meditation, meditation, and psychiatric medication before, I needed it now.

The morning of April 19, 2021 was a gorgeous day in Hampton, NH with the sun beaming off the ocean. After breakfast, I strapped on my running shoes to run three miles to my annual physical. It was not uncommon for me to literally ‘run my errands’. And why not run? Despite having latent chest pain for two years and myraid of medical consultations, procedures, and medical test, I was repeatedly told my heart was fine.

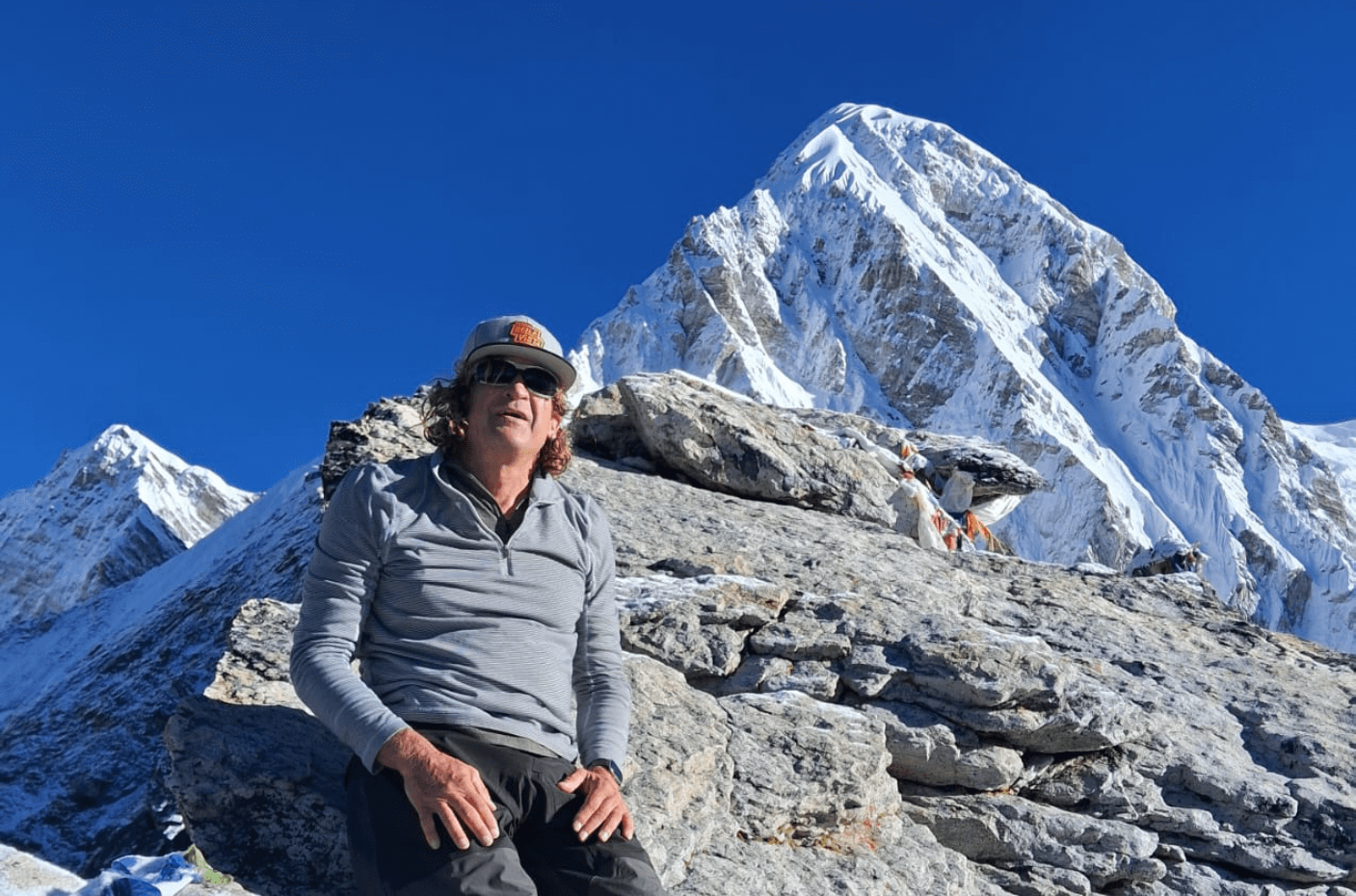

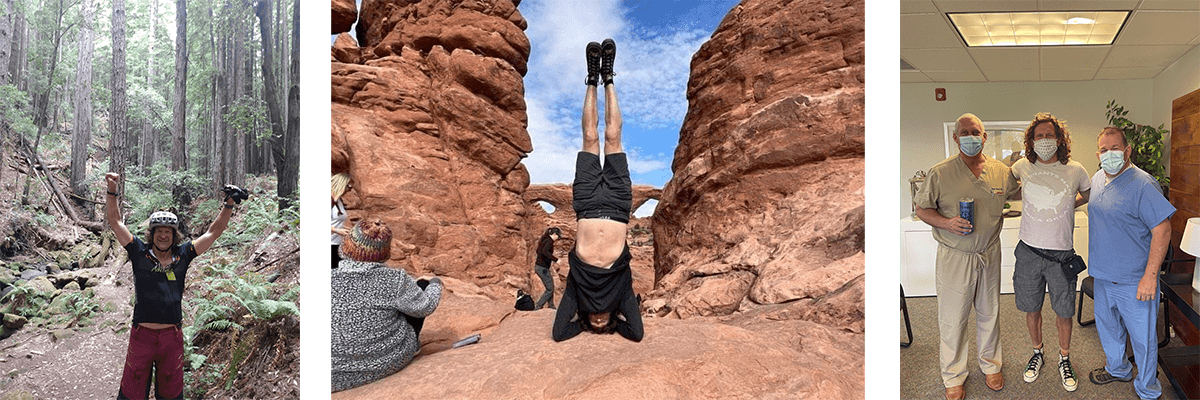

According to friends, family, I am a passionate person with fortitude, grit, and scrappiness. No adventure is too large or too small for me. I love to scuba dive, mountain bike, do yoga, play tennis and pickleball, golf, shoot pool, and play horseshoes. A plethora of co-workers called after the heart attack to express bewilderment that the “healthiest person they knew” had a massive heart attack. If it happened to me, they considered themselves doomed.

The signaling of imminent crisis ramified itself immediately during the run. I had to stop running after about a half mile in as I was out of breath, sweating, and experienced a sensation of low blood sugar. My first comment to the physicians assistant when she entered the exam room was, “Something is definitely wrong.” She ordered an EKG which I was told came back indicating my heart was fine. Suddenly an uncontrollable surge of ‘fight or flight’ overwhelmed me; I rushed out of the doctor’s office. The last thing I remember hearing was something about not checking out and a copay.

Up until I was writhing in pain in the parking lot of my primary physicians on the morning of April 19th, 2021, Two days before the heart attack, and a week too late, I was scheduled to have a batter of tests including a nuclear stress test in Raleigh. I was told six times by nurses, doctors, physician assistants, and paramedics during the heart attack that I was well, and nothing was wrong. Then I had a cardiac arrest …. A sense of doubt and distrust in medical professionals still permeates me today.

My first ride in an ambulance commenced with a vice grip on the paramedics hand, and asking him, “Am I going to die?” I thought ‘this is not good’ when there was no response. Pumped full of fentanyl and nitroglycerin I was feeling no pain when I arrived at Portsmouth hospital. My first semi-lucid recollection after the stent procedure was laying on a bed in excruciating chest pain as two nurses attaching EKG leads. One of the nurses calmly told me I just had a stent put in, and was experiencing discomfort from this procedure. I recall telling her, “Something is wrong, my chest is hurting….”. Acute stress response imbued me, and I attempted to escape from another unsafe situation. I came to life an hour later in a hospital room feeling like I had been run over by a Hunt Brothers semi-truck, five tubes sticking in my arms, and an EKG machine incessantly beeping. I vividly recall one incident during the stent procedure.

The massive wall of liquor was exquisitely displayed on a floor to ceiling mirror backed glass shelf. The bartender was dressed in vintage speakeasy attire with his back to the door. The bar was illuminated by natural light that consumed the room, but was not overwhelming or repulsive. One patron was in the bar. She sat at the mahogany bar half facing the doorway holding a whiskey with two cubes of ice. It was my mother who passed away a couple of decades ago. She was not beckoning me, or gesturing for me to leave. She had an ambivalent look on her face — an appearance of impartiality. Then my body violently convulsed on the metal table. Was that the after life, was it a vision induced by DMT coursing through my body, or was it a post temporal lobe phenomenon as Dr. Squee (a close friend) so eloquently portrayed.

What the hell just happened? Well, a lot. The bar vision, another incident of fight or flight, and oscillations between Vtach and VFib for eight minutes during cardiac arrest. After twelve jolts from a defibrillator, my ejection fraction (EF) measurement was fifteen, and my heart struggled to maintain rhythm. The attending nurse indicated, “You immediately became priority one in the hospital.” The stent was not adhered to the artery wall properly. This instigated a rethrombosis; the blockage went from 90% to 100%. Instead of being released from the hospital that afternoon, I would be agonizing over my heart ‘flipping a bit’ (Vtach), and incessantly ruminating that another heart attack was imminent.

The consistent stream of visitors and night nurse was what kept me in the game. Friends and family provided distraction, deflection, and inspiration. It helped me formulate a false positive narrative that allowed me to persevere. The night nurse spent hours with me. He was incredible; a sincere, honest, open, and compassionate human that was at the right place at the right time.

There were several more baffling, inexplicable, and horrifying health care moments while recuperating. The first happened two days after the heart attack. My heart was still consistently missing a beat; I could feel it. The hospital PA entered the hospital room to indicate I was going to be taken off two of the drips I was on. One of the drips helped abate the irregular heart beats—unsustained VTach. I was in distress, and immediately began to cry uncontrollably. I thought “what the f**k, this is not good.”. I flashed back to the ambulance when the paramedic did not respond to my question regarding my impending demise. “We are going to “roll the dice”, the hospital PA cavalry stated. She declared it was standard operating procedure (aka protocol) at the hospital. I don’t like, or believe in rules, this seemed to be a stupid rule to me.

The second agonizing incident occurred on the third day when I was cautioned by hospital staff there was a high probability I would need a pacemaker. This was a repercussion from the cardiac arrest. Perhaps it was the cold plunges in the New Hampshire ocean in February, the obsession with dietary regimens, or the hours spent on a meditation cushion, my EF had risen from 15 to 30 by the sixth day in the hospital. I was triumphantly capable of walking down a long hallway and up a flight of stairs, with a break. I was ready to be released! A few hours before release, the nurse nonchalantly mentioned, “You are lucky. This is the third time this has happened (rethrombosis) in the last two weeks. That is strange.”. I was released with a LifeVest that was costing me $3K a month as my insurance company decided it was not a necessary expenditure — I felt otherwise.

The arrival home was accompanied by balloons, a visit from the paramedics, and a multitude of friends and family. Help had arrived! The first friend to arrive came immediately after his son poignantly indicated, “If not now, when?”. It was sensational, inspiring, and comforting to be surrounded with love, kindness, and compassion from friends and family calling, sending gifts, and dropping off food. The power of connection was evident from dusk to dawn.

PTSD, anxiety disorders, or panic attacks were imaginary disorders to me. Now I am a believer. Sleep was implausible, daily panic attacks were persistent, and anxiety was pervasive throughout the day. PTSD consistently arose three times a night — my deceased mother ‘visited me’ on a few occasions. Natali was not allowed to leave my side, even when in the shower, napping, or taking a shit. She became proficient at watching me rest. I refused to do anything on my own. Walking two blocks to the beach was debilitating, and seeing the grossly unhealthy beach goers frolicking in the water, downing beers, and hitting the vape pipe added to my angst. My first encounter with a grocery store ended at the produce section; I am going to die was my thought as I rested on a crate of bananas.

Hope is restored, as my EF reaches fifty, and the vest is gone after one month. A miraculous recovery thanks to persistent twice daily three mile walks on the beach, sleeping twelve hours a day, breathing exercises, impromptu visits from friends, meditation, hours of gin rummy with Natali, and absence of work stress — work, what career? I even ventured out for lobster in Maine with my sister, and traveled an extravagant, apprehension-filled (where is the nearest hospital was an obsessive thought) excursion for dinner at a forest restaurant with a friend and my girlfriend Natali. Life was good!

After a move to Bella Vista, AR, the nightmares, distress, and indignation persisted. The emotional and mental recuperation was fleeting. Did my intellect get impaired while in cardiac arrest for 8 minutes? Was my balance impacted by the loss of blood flow to my brain during the cardiac arrest? I questioned my cognitive and physical coordination. Playing card games, darts, chess, shooting pool, or any activity invariably led me to question my ability to function at the same level I did prior to the heart attack. Taking life sustaining heart medication was aggravating. I took pride in “not being on anything” before the heart attack.

The mantra for the first year of recovery was, ‘This shit has to stop.’. Eradicate trepidation from life, and embrace a perspective of breaking all the rules. Even better — not see any rules to break, as there are not any rules. I resolved to start mountain biking beyond the 1.7 mile Tweeter Bird green trail circle. It was imperative to saturate myself in everything I had enjoyed before the heart incident. Natali and I embarked on an odyssey of scuba diving, hiking, motorcycle riding, snowboarding, four wheeling, snowmobiling, biking, and dancing in exotic distant lands and right at home in NWA.

Getting back to ‘normal’ — a new normal. This viewpoint made me happy, joyful, and optimistic the second year post heart attack. There is a time of play, a time to be born (again), a time to sow, and a time to reengage. My impulse after the heart attack was to say “f*** it” to work, and abandon all aspects of ‘normal’ life. Resisting the temptation to be controlled by the prefrontal cortex proved prudent. Life, including work, now had a purpose beyond achieving temporal success and pleasure. I took the time to appreciate those around me at work and play, and relax into the moment.

Four years plus post heart attack; life is, and will never be the same. I often recollect the salient, potentially inflammatory, comment a close friend Ale said to me in the Catskills during a visit to his place a couple months after the heart attack — “Maybe this was a good thing”. His compassionate candor was the truth. I would never wish what happened to me upon anyone.

Living through a death defying experience changes you, your life, your perspective of work, your connection to friends and family. If it doesn’t, you are suppressing your emotions or in denial. If you don’t embrace a normal, you are squandering an unprecedented, epic opportunity.

Life will never be the same — thankful. I am (still) here. On medicine, continuing to push the limits on a mountain bike, unwavering in my conviction, and resolute to challenge the conventional. Physically and emotionally more vulnerable and fragile — a good thing. There is merit to being able to overcome adversity, like a heart attack, but I am sure it is accompanied by a depletion of body and brain cells.

- Life is ephemeral and delicate : Prior to the heart attack I lived as though I was invincible, indestructible, and Life is fragile, precarious, and temporal. Cherish every moment with friends and family. Treat time and knowledge as the two most precious elements of life.

- Coping mechanisms are essential to recover : Physical activity was, and is, my dominant coping mechanism. It is demoralizing when your primary coping mechanism is no more—it has come back for me. Having more than one happy place, and more than one coping tool is crucial.

- Mind and body are one : Tales of the power of the mind, mind over matter, and broken heart syndrome are I have used will power, and possess the capacity to ignore pain, to achieve things. Psychosomatic symptoms were foreign to me before the heart attack — now I am a believer.

- PTSD and panic attacks are real : Humans best exhibit genuine empathy when they experience something themselves. I never had a PTSD incident or panic attack prior to my heart attack, therefore, these conditions didn’t exist in my ‘glass house’. Experiencing PTSD and panic attacks every day and night for months changed my perspective.

- Just breath : The power of breathing is unfathomable and baffling. The daily mid-afternoon, dusk, and night time panic episodes were usually abated and subdued by using the Apple Watch breathing application, or simple rhythmic I would lay down a quiet, dark location and breathe for ten to thirty minutes. My heart rate would plummet from over 100 beats a minute to 50, and my blood pressure would decrease from approximately 140/90 to 120/80.

- Get help, more help, and additional help (from professionals) : Friends and family are critical. A team consisting of a psychologist, physical therapist, psychiatrist, and cardiologist was essential. I can not phantom recovering mentally, emotionally, and spiritually with out the assistance of an SNRI. Resilience, positive thinking, meditation, breathing, spiritual retreats, cold showers, fishing, hiking, mountain biking, tenacity, and perseverance were Mind medication was the requisite ingredient to ‘bring it all home’. The teams at Dauntless Psychiatry and Northwest Rehab & Wellness — Bentonville were integral to the speed and magnitude of my mind and body recovery.

- Connection matters : Friends help with the physical, mental, and emotional Life without uninhibited, unconditional connection is a life devoid of warmth, pain, caring, suffering, giving, pleasure, receiving, and happiness.

- Adjusting to medicine takes time : Taking medication for the rest of my life is depressing enough. The medicine does affect you. It affects you physically, mentally, and emotionally. Try different regimens, different brands, and swap mornings and evenings. Some people will tell you it has been proven certain medications have side effects that are worse than the remedy. This definitive, factual (mis)information most likely comes from social media posts, podcasts, pseudo physicians, and charlatans. Without the medicine, I will die — that is the truth.

- Accountability is rare, apologies are even rarer : There is limited truth telling in the healthcare field. Why should the healthcare field be any different than any other vocation? Mistakes need to be suppressed, or people lose their livelihoods. Leaders and ‘experts’ in particular are sensitive to exposing themselves to, and distancing themselves from, mishaps. Don’t expect anyone to say sorry, or ‘I made a mistake’.

- Get a haircut and dress nice : I was asked at most every doctor’s visit if I was employed and/or had insurance. I was even asked if I had a home a few times. All because I have long hair, an earring, and wear a t-shirt, shorts, and Prejudice is rampant. People will treat you differently if you don’t look and act like they do. Fortunately, I know people that know people that respect me for me.

- Financial and career safety net matters : Amazon has been gracious and The conventional financial wisdom is to have six months of monetary safety net. I adhere to the dogma of a one year safety net. I built a reputation for delivering results and delighting customers — career security. Not having to worry about paying for out of pocket expenses, not having the pressure to work, and having the luxury to spend time recovering were essential. I witnessed too many people in physical therapy that had the added stress of paying the mortgage and working long hours to maintain their jobs.

- Friends in ‘high places’ : The adage “who you know is as important as what you know” is a maxim that resonated with me after the heart Each individual in health care is literally a number. I take a ticket each time I visit the cardiologist. We are all snowflakes. The medical system treats each individual identically. Having people that know you, believe in you, and have the power to help you is mandatory.

- The US Healthcare system isBullShit : The US healthcare system is reactive, volume based, ‘show me the money’, and impersonal. Doctors don’t have the time to listen, and are reluctant to do procedures not covered by insurance The book Outlive: The Science and Art of Longevity is an expose that elaborates on the triumphs of modern medicine, and exposes the failures of the last 30 years. Medicine has not evolved much since the discovery that germs cause infection, and penicillin can stymie bacterial infections. Antibiotics have extended the average human lifespan by 23 years over the 100 years. US health care has made minuscule progress since the discovery of antibiotics.

- Taking it to fourteen, writing is cathartic : Writing has always been a creative, calming, and inspirational act for Writing about a personal calamity elucidates latent emotions of gratitude, regret, appreciation, kinship, and somberness. Recollecting and recounting a catastrophe is a means to move beyond, provoke a few daemons, and scare a few monsters in my head.

Life is a brittle, ephemeral phenomenon with a series of seemingly random events that we build a narrative around to keep us sane. This is a story of missed opportunities, mishaps, misdirection, and unpredictable consequences. A story that encapsulates and epitomizes life. You rarely get second chances — seize them, don’t let them slip away. It is good to be back, and “It could have been worse.” — Book by A.H. Benjamin

Tom’s Heart Attack Recovery Timeline: Widowmaker Survivor Story